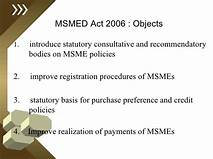

MSME ACT: OBJECT & IMPACT

Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises

Development Act, 2006 (In

short “MSME Act”) was enacted with the

object of facilitating the promotion, development and enhancing the

competitiveness of small and medium enterprises. The Act inter alia define “small enterprise” and medium enterprise and provides

for establishment of a National Small and Medium Enterprises Board, besides, it

provide for classification of small and medium enterprises on the basis of

investment in plant and machinery or equipment or establishment of Advisory Committee. What is of

pertinence is that the MSME Act encapsulates provisions for ensuring timely and

smooth flow of credit to small and medium enterprises to minimize the incidence

of sickness in accordance with the Guidelines of Reserve Bank of India (RBI). The MSME Act has faced impediments in

its way, and the object sought to be achieved has been achieved, but only

partially.

THE

PROVISIONS

Chapter

V of the said MSME Act (sections 15 to 24) contains provisions to address the

issue of delayed payment to Micro and Small Enterprises. Section 15 of the Act

mandates that where any supplier supplies any goods or renders any services to

any buyer, the buyer would make the payment for the same on or before the date

agreed, which in any case could not exceed 45 days from the date of

acceptance/deemed acceptance. Section 16 of the Act provides for payment of

interest. Section 17 of the Act mandates that the buyer would be liable to pay

the amount for the goods supplied or services rendered along with interest as

provided under Section 16 of the Act. 10.

Section

18(1) of the Act contains a non obstante clause and enables any party to a

dispute to make a reference to the Micro and Small Enterprises Facilitation

Council (MSEFC).

If

one examines the scheme of the provision of Section 15 to 23 of the Act, it is

apparent that the scheme is to provide a statutory framework for Micro and

Small Enterprises to expeditiously recover the amounts due for supplies made by

them. This is in conformity with the object of the Act to minimize the

incidence of sickness in Small and Medium Enterprises and to enhance their

competitiveness. It is understood that the Small and Medium Enterprises do not

command a significant bargaining power and to thus it is indicated in the

statement of object and reasons of the Act - the object of the Act is, inter

alia, to extend the policy support and provide appropriate legal framework

for the sector to facilitate its growth and development.

ARBITRATION AS PER MSME ACT

It

is, apparently, for this reason that Section 18 (3) does not contemplate an Arbitration

to be conducted by an Arbitrator which is to be appointed by either party, but

expressly provides that the same would be conducted by MSEFC or by any

institution or a centre providing alternate dispute resolution services.

Section

19 of the Act also ensures a more expedient recovery by making pre-deposit of

75% of the awarded amount, a pre condition for assailing the award. It is

necessary to point out that the benefit of this provision is also available in

case of arbitrations in terms of agreements between the parties (and not by a statutory

reference under Section 18 (3) of the Act). As per the law evolved and shall be

discussed subsequently. It is so, as the MSME Act overrides the other law for

the time being in force. Section 24 may be perused in this regard:

Section 24 of MSME Act has Overriding effect-

24.

The provision of sections 15 to 23 shall have effect notwithstanding anything

inconsistent therewith contained in any other law for the time being in force.”

A plain reading of Section 18(2) of the Act

indicates that on receipt of a reference under Section 18(1) of the Act, the

Council [MSEFC] would either conduct conciliation in the matter or seek

assistance of any institution or centre providing alternate dispute resolution

services. It also expressly provides that Section 65 to 81 of the Arbitration

& Conciliation Act (A& C) 1996 Act, would apply to such a dispute as it

applies to conciliation initiated under the Part III of the A&C Act. It is

clear from the provisions of Section 18 (2) of the Act that the legislative

intention is to incorporate by reference the provisions of Section 65 to 81 of

the A&C Act to the conciliation proceedings conducted by MSEFC.

Section

18 (3) of the Act expressly provides that in the event the conciliation

initiated under Section 18 (2) of the Act does not fructify into any

settlement, MSEFC would take up the disputes or refer the same to any

institution or centre providing alternate dispute resolution services for such

arbitration.

LAW:

AS EVOLVED

PIYA BAJWA Vs

MICRO AND SMALL ENTERPRISES FACILITION CENTRE AND ANR. W.P.(C)

1134/2021 & CMAPPL. 3201/2021

The hon’ble Delhi high court in the above case had

occasion to deal with the following communication issued by the Micro and Small

Enterprises Facilitation Council (MSEFC) by which the Petitioner was

called to participate in the conciliation process and also file a reply. The impugned communication issued by the

Facilitation Council dated 31st December, 2020 reads as under:

“The MSEF Council, Delhi is in receipt of a reference filed

u/s 18(1) of the MSMED Act, 2006 by the Claimant M/s Sharp Travels (India)

Ltd., Application/Temp No. DL08E0001555/S/00122 against the outstanding dues of

Rs. 308307 which is to be paid by you to the Claimant. I am directed to inform

you that the MSEF Council, Delhi has decided that the conciliation process

should be taken up first before release of outstanding dues to the Claimant,

failing which a Notice to personally appear before the Council will be served

to you for taking further necessary action in the matter. Further, I am to

inform you that as per Section 16 of the MSMED Act, 2006 the Respondent will be

liable to pay the compound interest with monthly rests to the supplier on that amount

from the appointed day or, as the case may be, from the date immediately

following the date agreed upon, at three times of the bank rate notified by the

Reserve Bank. It is therefore requested to file the reply of outcome of the

conciliation process held between both of you within 30 days.”

The

petitioner in the writ petition had assailed that and pointed out that the

words “decided that” clearly implied that Facilitation Council has taken

a decision in the matter that the Petitioner ought to release the outstanding

dues, whereas the claim is time barred

and thus, such a decision could not have been taken without hearing the

Petitioner. As the claim itself was not maintainable, therefore, proceeding

further was uncalled for. Per contra, it was the contention of respondent that

the mere fact that the Facilitation Council has called the parties for

exploring conciliation in terms of Sections 18(1) and 18(2) of the Micro, Small

and Medium Enterprises Development Act, 2006 does not imply that any decision

was taken. In case, the conciliation process fails then the remedies of the

Petitioners are available in terms of Sections 18(3) and (4) of the MSME Act.

The conciliation process is meant to resolve the disputes between the parties

in an amicable manner. The petitioner therefore cannot be forced to enter into a settlement with Respondent .

ARBITRATION ACT AND MSME ACT: IS THERE OVERLAP?

The

scheme of the MSME Act has been discussed in detail in the judgment of a ld.

Single Judge of hon’ble Delhi High Court in BHEL vs. The Micro and Small

Enterprises Facilitation Centre & Anr., [W.P.(C) 10886/2016, decided on 18th September, 2017]. The Court observed therein as under:

A plain reading of Section 18(2) of the

Act indicates that on receipt of a reference under Section 18(1) of the Act,

the Council [MSEFC] would either conduct conciliation in the matter or seek

assistance of any institution or centre providing alternate dispute resolution

services. It also expressly provides that Section 65 to 81 of the A&C Act

would apply to such a dispute as it applies to conciliation initiated under the

Part III of the A&C Act.

It is clear from

the provisions of Section 18(2 of the Act that the legislative intention is to incorporate

by reference the provisions of Section 65 to 81 of the A&C Act to the

conciliation proceedings conducted by MSEFC. Section 18(3) of the Act expressly

provides that in the event the conciliation initiated under Section 18(2) of

the Act does not fructify into any settlement, MSEFC would take up the disputes

or refer the same to any institution or centre providing alternate dispute

resolution services for such arbitration.

In paragraph 17, it is held that

“It is at once

clear that the provision of Section 18(3) of the Act do not leave any scope for

a non institutional arbitration. In terms of Section 18(3) of the Act, it is

necessary that the arbitration be conducted under aegis of an

institution-either by MSEFC or under the aegis of any “Institution or Centre

providing alternate dispute resolution services for such arbitration”.”

Interestingly,

the Bombay High Court in the case of M/s Steel Authority of India v. The Micro,

Small Enterprise Facilitation Council and Anr. : AIR 2012 Bom 178

held in paragraph 11 of the said judgment, that “we find that there

is no provision in the Act, which negates or renders the arbitration agreement

entered between the parties ineffective”.

The Punjab and Haryana High Court in The

Chief Administrative, COFMOW (supra) had rejected the contention

that provisions of Section 18 (3) of the Act for referring the disputes to

arbitration would apply only where there was no arbitration agreement between

the parties.

However, Punjab & Haryana High Court

in Welspun Corp. Ltd v. The Micro and Small, Medium Enterprises

Facilitation Council, Punjab and others :CWP No. 23016/2011

decided on 13.12.2011, had taken a view contrary to that of the Bombay

High Court. Similarly, the decision of the Madras High Court in M/s Refex

Energy Limited v. Union of India and Another : AIR 2016 Mad139 was also on the

line of welspun (Supra)

The

judgment rendered by Allahabad High Court in BHEL v. State of U.P. and

Others : W.P. (C) 11535/2014 decided on 24.02.2014; the decision of the Calcutta High Court in NPCC

Limited and another v. West Bengal State MSEFC & Ors.: GA No.

304/2017 W.P. 294/2016 decided on 16.02.2017; and the decision of Delhi

High Court in GE T & D India Ltd. v. Reliable Engineering Projects

and Marketing : OMP (Comm.) No. 76/2016 decided on 15.02.2017,

are on similar line and contrary to

Bombay High Court.

The

Calcutta High Court in the case of National projects Construction

Corporation Limited (supra) had also concluded that in cases

where an arbitration agreement existed between two parties and one such party

was an entity within the meaning of the Act, the Council established under the

Act would have jurisdiction to arbitrate the disputes between such parties. The

Court further observed as under:-

“When there exists an

arbitration agreement between two parties and one of such parties to the

arbitration agreement is an entity within the meaning of the Act of 2006, the

Council established under the provisions of the Act of 2006 or any institution

or centre identified by it has the jurisdiction to arbitrate such disputes on a

request being received by such Council for such purpose”.

The

Supreme Court in National Seeds Corporation Ltd v. M. Madhusudhan Reddy

& Anr. : (2012) 2 SCC 506 has held that the MSME Act

being a Special Act would override the provisions of Arbitration and

Conciliation Act, 1996 (hereafter the 'A&C Act').

It is thus

clear through catena of judicial precedents that even when there may be

arbitration agreement between the parties, but in view of non obstante clause

in MSME Act and the fact that the MSME Act is a special enactment, the

provision of MSME Act shall prevail and the arbitration, if allowed to

comm3ence upon failure of amicable settlement, the same shall be under the aegis

of MSME Act only.

OVEREMPHASIS

ON THE WORD SUPPLIER

The MSME

Act however overemphasize “supplier” and “buyer” and buyer is perceived to be

liable, though section 18 somewhat clears the air, in as much as it is

specified that “any party to a dispute” with

regard to any amount due may make a reference for a sum due u/s 17 of the MSME

Act before the Micro and Small Enterprises Facilitation Council (MSEFC). The

classification of “supplier” and “buyer” category is inadequate in as much as

there may be several instance where the buyer may be in receiving ends from a

supplier, which may be a big establishment and may dictate their terms and thus

overemphasis on buyer being liable to supplier is something which deserve a

relook. Similarly, the issue of jurisdiction or exclusive jurisdiction is

somewhat ambiguous under the MSME Act in as much as, whereas the situs of

jurisdiction shall be the location of “supplier” but in similar vein it is also written and buyer all over the country. It

is though vague, whether buyer shall be entitled to raise a claim in their

location itself or not? The section 18(4) may be perused in this regard:

(4) Notwithstanding anything contained

in any other law for the time being in force, the Micro and Small Enterprises

Facilitation Council or the centre providing alternate dispute resolution

services shall have jurisdiction to act as an Arbitrator or Conciliator under

this Section in a dispute between the supplier located within its jurisdiction

and a buyer located anywhere in India.

The

ambiguity, therefore crave for rectification.

REMARK

The MSME Act and MSEFC constituted under it has travelled

some distance and provisions are made in the Act not only to promote MSME

organization, but some leverage is accorded to them for seeking speedy

redressal of their grievance, still, the gaping holes in the Act need to be

plugged and some more teeth may be given to the MSEFC under the MSME Act. Besides,

overemphasis on “supplier” and “buyer” and showing buyer as liable is

incomplete depiction or assumptive of a situation. There may be instance, where

buyers could be in receiving end, though, what is inherent in the Act is that

buyer shall be liable and otherwise also liability upon buyer is fastened in

terms of the Act. This is oversimplification and the aggrieved party needs to

be clearly defined and that could be buyer or supplier or any other entity. The

issue of jurisdiction , particularly, the territorial jurisdiction as per the Section

18(4) of the MSME Act need to be clearly specified to make it more explicit and

to undo the vagueness..

Anil

K Khaware

Founder

& Senior Associate

Societylawandjustice.com